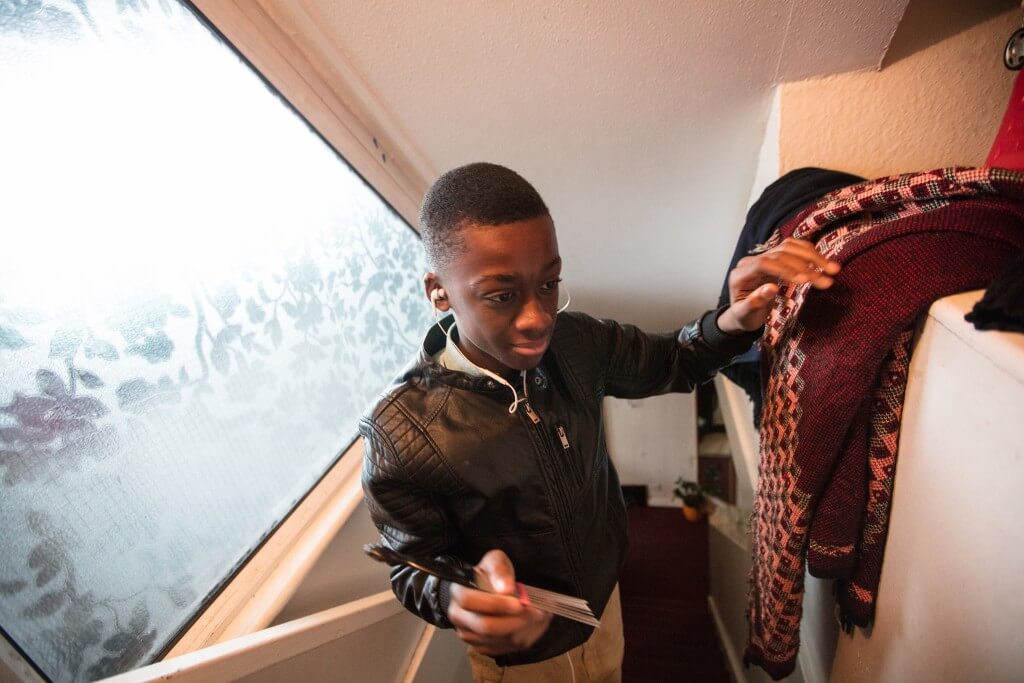

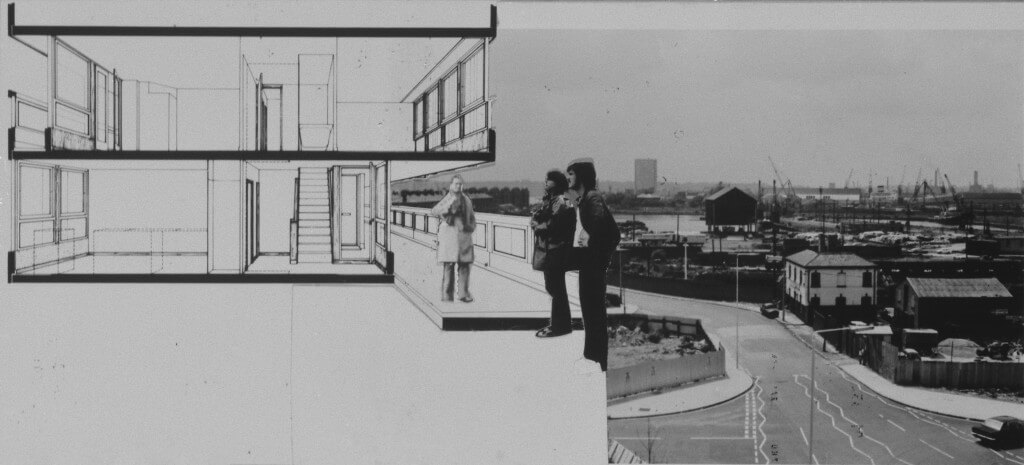

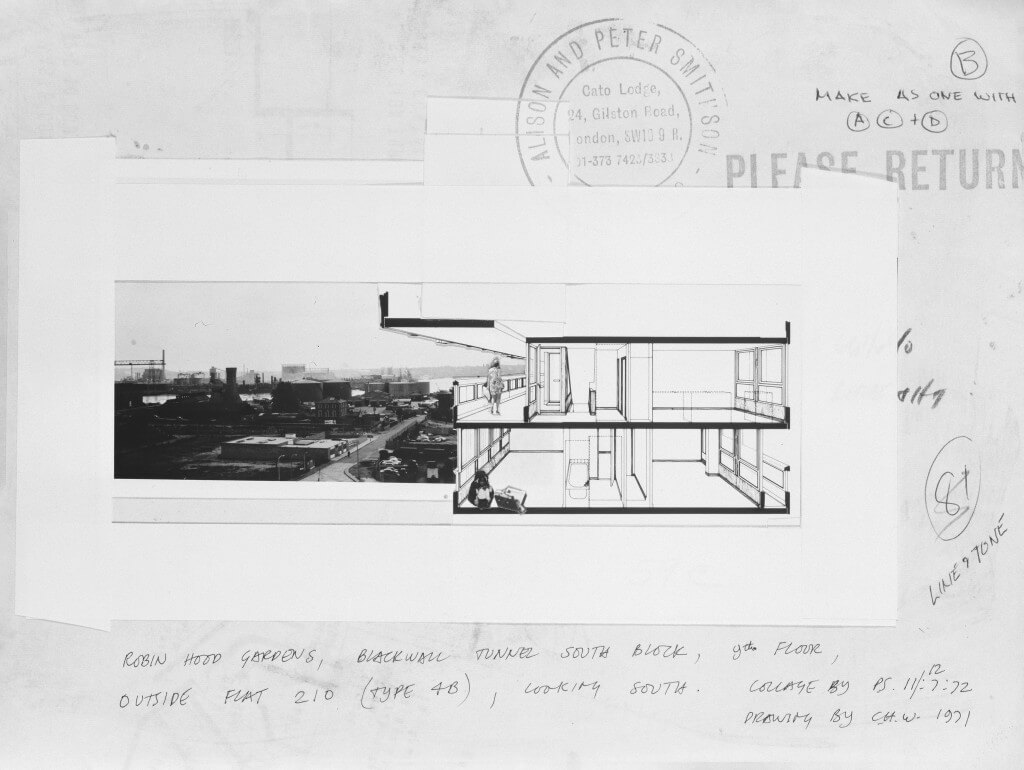

The looming, logo-topped towers of Canary Wharf’s banks are an icon and instance of the finance-driven regeneration that long threatened Robin Hood Gardens. The west block of the estate, demolished in 2017/18, appears here to physically hold back these encroaching forces, forces which resident Darren Pauling described to the local press, turning the tables on the usual pejorative use of “concrete” to condemn the estate.

“I’m sick of concrete jungle creeping up on Robin Hood Gardens,” he wrote. “I have lived on the Robin Hood Gardens estate for over a decade and in Poplar all of my life. I love where I live.” Darren showed the flaws in the council and developer’s partial polling of residents about their preferences for the estate’s future. They refused to hold a formal ballot, so he organised a survey where 130 families out of 140 surveyed wanted refurbishment not demolition.